Freshwater Legislation in New Zealand

Local authorities get direction from:

- National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management 2020 (NPS-FM)

- National Environmental Standards for Freshwater

- Stock exclusion regulations

- Water measurement and reporting regulations

This section provides an overview of the legislation and their requirements for freshwater. All information presented here is sourced from the Ministry for the Environment. To ensure the most up to date legislative information, we refer readers directly to the Ministry for the Environment.

This section does not include legislation from local government authorities. For specific regional rules and regulations, we refer readers directly to their regional authority.

What do I need to do on my farm?

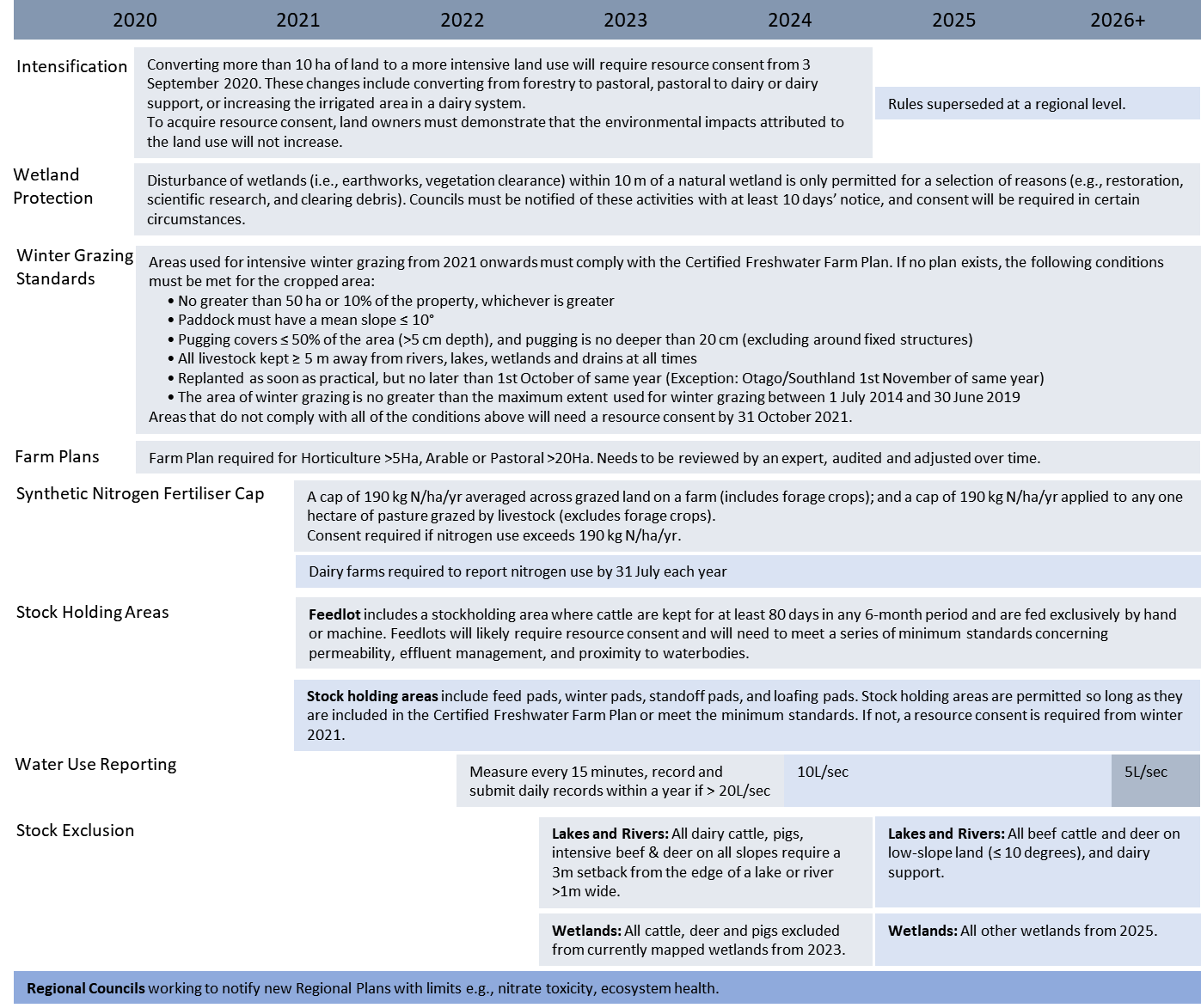

This table summarises the legislative requirements for farmers and growers and when they come into effect.

What is the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management (NPS-FM)?

The NPS-FM came into force on 3 September 2020 and replaced the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management 2014 (as amended in 2017).

The requirements of the Freshwater NPS (2020) include:

Manage freshwater in a way that ‘gives effect’ to Te Mana o te Wai:

- Through involving tangata whenua

- Working with tangata whenua and communities to set out long-term visions in the regional policy statement

- Prioritising the health and wellbeing of water bodies, then the essential needs of people, followed by other uses.

Improve degraded water bodies and maintain or improve all others using bottom lines defined in the Freshwater NPS.

An expanded National Objectives Framework:

There are now four compulsory values. Ecosystem health and human health for recreation and the newly added threatened species and mahinga kai.

Councils must develop plan objectives that describe the environmental outcome sought for all values (including an objective for each of the five individual components of ecosystem health).

The 2020 version introduces new attributes, aimed specifically at providing for ecosystem health, include fish index of biotic integrity (IBI), sediment, macroinvertebrates (MCI and QMCI), dissolved oxygen, ecosystem metabolism and submerged plants in lakes. Councils will have to develop action plans and/or set limits on resource use to achieve these attributes.

Tougher national bottom lines for the ammonia and nitrate toxicity attributes to protect 95% of species from toxic effects (up from 80%).

Avoid any further loss or degradation of wetlands and streams, map existing wetlands and encourage their restoration.

Identify and work towards target outcomes for fish abundance, diversity and passage and address in-stream barriers to fish passage over time.

Set an aquatic life objective for fish and address in-stream barriers to fish passage over time.

Monitor and report annually on freshwater (including the data used); publish a synthesis report every five years containing a single ecosystem health score and respond to any deterioration.

More detail on this National Policy Statement is available from the Ministry for the Environment.

What is Te Mana o te Wai?

Te Mana o te Wai refers to the vital importance of water.

When managing freshwater, it ensures the health and well-being of the water is protected and human health needs are provided for before enabling other uses of water. It expresses the special connection all New Zealanders have with freshwater. By protecting the health and well-being of our freshwater we protect the health and well-being of our people and environments. Through engagement and discussion, regional councils, communities and tangata whenua will determine how Te Mana o te Wai is applied locally in freshwater management.

Watch a video from the Ministry for the Environment that provides an overview of Te Mana o Te Wai.

The NPS-FM 2020 strengthens and clarifies Te Mana o te Wai by providing stronger direction on how Te Mana o te Wai should be applied when managing freshwater.

Te Mana o te Wai must inform how the NPS-FM 2020 is implemented

Te Mana o te Wai imposes a hierarchy of obligations. This hierarchy means prioritising the health and well-being of water first. The second priority is the health needs of people (such as drinking water) and the third is the ability of people and communities to provide for their social, economic, and cultural well-being. The hierarchy does not mean, however, that in every case the water needs to be restored to a pristine or prehuman contact state before the other needs in the hierarchy can be addressed.

The six principles of Te Mana o te Wai in the NPS-FM 2020 inform its implementation

Mana whakahaere: the power, authority, and obligations of tangata whenua to make decisions that maintain, protect, and sustain the health and well-being of, and their relationship with, freshwater.

Kaitiakitanga: the obligation of tangata whenua to preserve, restore, enhance, and sustainably use freshwater for the benefit of present and future generations.

Manaakitanga: the process by which tangata whenua show respect, generosity, and care for freshwater and for others.

Governance: the responsibility of those with authority for making decisions about freshwater to do so in a way that prioritises the health and well-being of freshwater now and into the future.

Stewardship: the obligation of all New Zealanders to manage freshwater in a way that ensures it sustains present and future generations.

Care and respect: the responsibility of all New Zealanders to care for freshwater in providing for the health of the nation.

Giving effect to Te Mana o te Wai

Regional councils must give effect to Te Mana o te Wai by actioning the five key requirements of Te Mana o te Wai. These are shown in the figure below.

How regional councils must give effect to Te Mana o te Wai.

Long-term visions for freshwater To give effect to Te Mana o te Wai regional councils must develop a long-term vision through discussion with communities and tangata whenua. Establishing a long-term vision for a waterbody means capturing the needs and aspirations of the community and tangata whenua in each region. Long-term visions identify a time frame that is both ambitious and reasonable (for example 30 years).

The long-term vision needs to be based on the history of, and current pressures, on local waterbodies and catchments. Regional councils also need to regularly report on their progress against the long-term vision.

Tangata whenua involvement

Local authorities must actively involve tangata whenua in freshwater management (including decision-making processes, and monitoring and preparation of policy statements and plans). Regional councils must investigate the use of tools in the Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA) such as joint management arrangements, Mana Whakahono ā Rohe, and transfer of powers – as a way of involving tangata whenua.

Integrated management

Local authorities must take an integrated management approach to freshwater management in accordance with the principle of ki uta ki tai (‘from the mountains to the sea’). This principle recognises the interconnectedness of the environment, the interactions between its parts, and requires integration between freshwater management and land use to avoid adverse effects (including cumulative effects) on the health and well-being of freshwater environments.

As key land users in catchments, farmers and growers must manage land in relation to waterways in a way that complies with how Te Mana o te Wai is given effect to locally. In order to give effect to Te Mana o te Wai, regional councils will develop rules for land use and freshwater use that farmers and growers need to follow. Farmers and growers will be able to be part of this process through regional council plan development.

Watch a short video from the Ministry for the Environment that discusses how councils must give effect to Te Mana o Te Wai.

What is the National Objectives Framework?

The National Objectives Framework (NOF) in the NPS-FM (2020) sets up requirements for regional councils and unitary authorities in setting objectives, policies, and rules to manage freshwater in their regions.

The framework firstly requires regional councils to establish what values apply to the freshwater bodies in their region. As a starting point, the Government has set four compulsory national values that must be provided for everywhere (NPS-FM 2020 Appendix 1). These are described in more detail below.

To assess if a water body meets the value, the state of the water is assessed using attributes (Appendix 2 of the NPS-FM). An attribute is a measurable characteristic (numeric, narrative, or both) that can be used to assess the extent to which a particular value is provided for. They are typically assessed at long-term water quality monitoring sites. The NOF provides directive of how the data is to be assessed and minimum sample requirements (e.g., median and 95% percentile of 5 years of monthly samples or a minimum of 60 samples.

These attributes can be used by the regional council to define acceptable limits on resource use. A limit is the maximum amount of “resource use” that is possible, while still meeting the freshwater objective to maintain or improve the waterbody over time. The methods used by the council describe the actions required to achieve the limit and may be regulatory or non‑regulatory. These methods will vary between regions as they are at the discretion of each regional authority.

The local authority will have defined Freshwater Management Units (or FMU) for freshwater management and accounting purposes. It is at this scale that local rules may apply.

Compulsory National Objectives Framework Values

Ecosystem health

This refers to the extent to which an FMU or part of an FMU supports an ecosystem appropriate to the type of water body (for example, river, lake, wetland, or aquifer).

There are 5 biophysical components that contribute to freshwater ecosystem health, and it is necessary that all of them are managed. They are:

Water quality – the physical and chemical measures of the water, such as temperature, dissolved oxygen, pH, suspended sediment, nutrients, and toxicants.

Water quantity – the extent and variability in the level or flow of water.

Habitat – the physical form, structure, and extent of the water body, its bed, banks and margins; its riparian vegetation; and its connections to the floodplain and to groundwater.

Aquatic life – the abundance and diversity of biota including microbes, invertebrates, plants, fish and birds.

Ecological processes – the interactions among biota and their physical and chemical environment such as primary production, decomposition, nutrient cycling and trophic connectivity.

In a healthy freshwater ecosystem, all 5 biophysical components are suitable to sustain the indigenous aquatic life expected in the absence of human disturbance or alteration (before providing for other values).

Human contact

This refers to the extent to which an FMU or part of an FMU supports people being able to connect with the water through a range of activities such as swimming, waka, boating, fishing, mahinga kai, and water skiing, in a range of different flows or levels. Matters to take into account include pathogens, water clarity, deposited sediment, plant growth (from macrophytes to periphyton to phytoplankton), cyanobacteria, other toxicants, and litter.

Threatened species

This refers to the extent to which an FMU or part of an FMU that supports a population of threatened species has the critical habitats and conditions necessary to support the presence, abundance, survival, and recovery of the threatened species. All the components of ecosystem health must be managed, as well as (if appropriate) specialised habitat or conditions needed for only part of the life cycle of the threatened species.

Mahinga kai

Mahinga kai – kai is safe to harvest and eat.

Mahinga kai generally refers to freshwater species that have traditionally been used as food, tools, or other resources. It also refers to the places those species are found and to the act of catching or harvesting them. Mahinga kai provide food for the people of the rohe and these sites give an indication of the overall health of the water. For this value, kai would be safe to harvest and eat. Transfer of knowledge is able to occur about the preparation, storage and cooking of kai. In FMUs or parts of FMUs that are used for providing mahinga kai, the desired species are plentiful enough for long-term harvest and the range of desired species is present across all life stages.

Mahinga kai – Kei te ora te mauri (the mauri of the place is intact).

In FMUs or parts of FMUs that are valued for providing mahinga kai, customary resources are available for use, customary practices are able to be exercised to the extent desired, and tikanga and preferred methods are able to be practised.

Other NOF Values

There are also other values that must be considered. These include:

- Natural form and character

- Drinking water supply

- Wai tapu

- Transport and Tauranga waka

- Fishing

- Hydro-electric power generation

- Animal drinking water

- Irrigation, cultivation, and production of food and beverages

- Commercial and industrial use

More information on these other values provided in the NPS-FM 2020 (Appendix 1B) available from the Ministry for the Environment.

How is the state of a water body determined to be meeting values?

The NOF contains tables for all attributes used to assess if the waterbody is meeting the compulsory values (Appendix 2 NPS-FM). It essentially tells you what to measure (attribute), how it is to be analysed, and how many samples are required to assess the state of the water body. These are called attributes requiring limits on resource use.

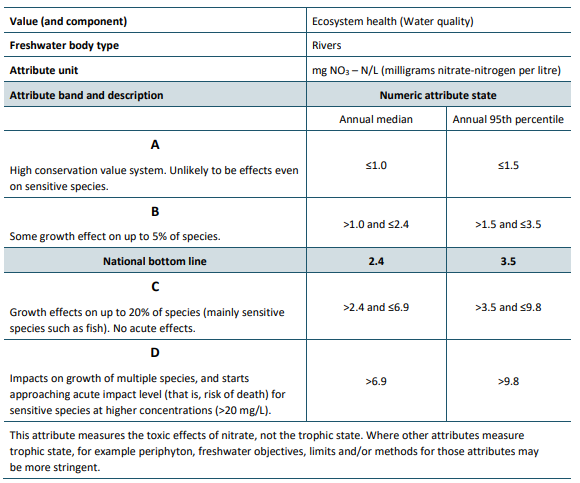

Attributes requiring limits on resource use

The attribute state at the monitoring site is classified into bands (A – E) according to the NOF. Each band has a narrative description of the state and a numeric value to assess measured data against. The attribute table for nitrate nitrogen in rivers is provided below as an example.

For some attributes, the Government has outlined a minimum acceptable physical state. This is known as the national bottom line. All water bodies failing this national bottom line are required to be improved to a minimum of the national bottom line.

What methods, regulation and rules to maintain or improve water quality is then up to the discretion of each council.

More information on these attributes are provided within the NPS-FM 2020 (Appendix 2) available from the Ministry for the Environment.

What is a Freshwater Management Unit (FMU)?

Central government’s NPS-FM 2020 directs regional councils to identify areas called Freshwater Management Units (FMUs).

An FMU can be a water body, multiple water bodies or any part of a water body determined to be the appropriate scale for setting freshwater objectives and limits. The definition of FMUs is intentionally flexible so councils can determine the spatial scale best suited to managing fresh water in the specific circumstances of their region.

What are the National Environmental Standards for Freshwater (NES-FW)?

The standards regulate activities that pose risks to the health of freshwater and freshwater ecosystems. The Freshwater NES set requirements for carrying out certain activities that pose risks to freshwater and freshwater ecosystems. Anyone carrying out these activities will need to comply with the standards.

The standards are designed to:

- Protect existing inland and coastal wetlands

- Protect urban and rural streams from in-filling

- Ensure connectivity of fish habitat (fish passage)

- Set minimum requirements for feedlots and other stockholding areas

- Improve poor practice intensive winter grazing of forage crops

- Restrict further agricultural intensification until the end of 2024

- Limit the discharge of synthetic nitrogen fertiliser to land and require reporting of fertiliser use.

In many cases, people will need to apply for a resource consent from their regional council to continue carrying out regulated activities.

The standards came into force in September 2020 for the majority of the regulations. Requirements for intensive winter grazing (subpart 3 of Part 2), and stockholding areas other than feedlots (regulations 12-14) and the application of synthetic nitrogen fertiliser to pastoral land (subpart 4 of Part 2) come into force in May and July 2021, respectively.

More detail on the National Environmental Standards for Freshwater is available from the Ministry for the Environment.

What are the Stock Exclusion Regulations?

The stock exclusion regulations prohibit the access of cattle, pigs and deer to wetlands, lakes, and rivers. These regulations were developed as part of the Essential Freshwater work programme. The purpose of the regulation is to reduce the impact of damage to our waterways from livestock.

When livestock enter water bodies, they contaminate the water and damage the banks. This compromises New Zealanders’ ability to use waterbodies for recreation and mahinga kai (food gathering). Heavy livestock (cattle and deer) and pigs have the greatest impact. Livestock can carry disease-causing organisms like campylobacter, which can make people sick when they come into contact with water contaminated with livestock dung. Dung and urine also contain nutrients that promote weed growth and decrease the water body’s ability to support a healthy ecosystem. When stock trample banks and beds of water bodies they increase streambank erosion and sediment runoff. This has an adverse effect on habitats including those used for fish spawning.

About the regulations:

These regulations came into force on 3 September 2020 and apply to a person who owns or controls beef cattle, dairy cattle, dairy support cattle, deer, or pigs (stock).

The regulations require the person to exclude stock from specified wetlands, lakes, and rivers more than one metre wide.

Dairy cattle, dairy support cattle, and pigs must be excluded from the water bodies regardless of the terrain.

Beef cattle and deer must be excluded from the water bodies regardless of terrain if they are break-feeding or grazing annual forage crops or irrigated pasture. Otherwise, the requirements apply to beef cattle and deer only on mapped low slope land.

Stock must be excluded from the beds of lakes, rivers, and wetlands, and must not be on land closer than three metres to the bed of rivers and lakes. However, stock need not be excluded from land within three metres of the bed if there is a permanent fence in place on 3 September 2020.

Stock, except deer, may only cross a river or lake by using a dedicated bridge or culvert, unless they cross no more than twice in any month. The regulation sets out specified circumstances when cattle and pigs can cross without a dedicated culvert or bridge. Deer are not subject to restrictions for crossing rivers and lakes.

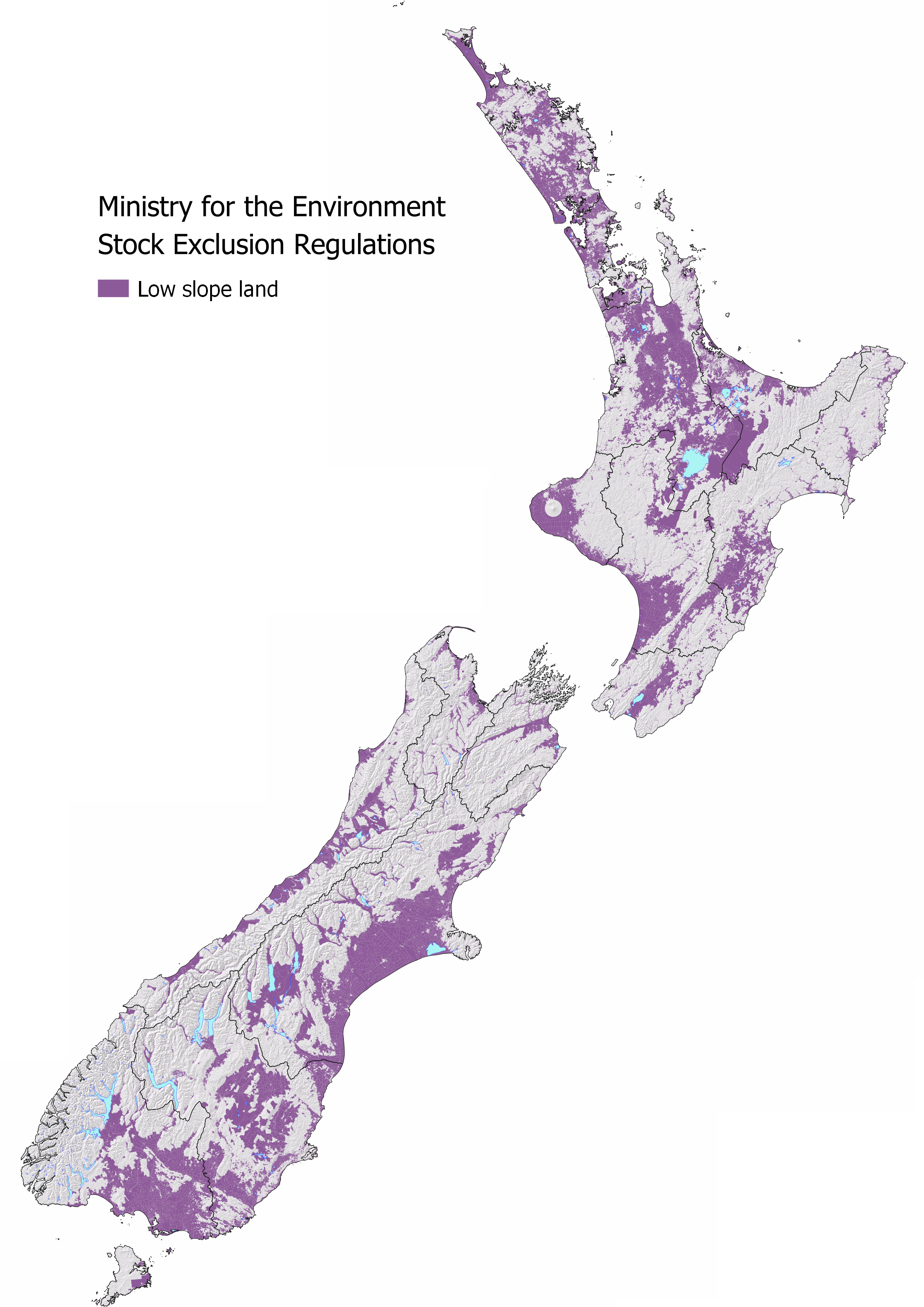

Low Slope Land

The low slope land maps are part of the regulation. These maps are available in the MAPS. This data set was created by the Ministry for the Environment with support from Manaaki Whenua - Landcare Research in the selection of elevation model and method for calculating the slope layer.

The area the Ministry for the Environment classifies as low slope land is illustrated here.

Data Source: Ministry for the Environment (2020).

The mapped areas show low slope land where beef cattle and deer must be excluded from lakes and rivers over one metre wide from 1 July 2025. The mapped areas also show where all cattle, pigs and deer must be excluded from natural wetlands with an area more than 500 square metres from 1 July 2025.

The maps show land with an average slope less than or equal to 10 degrees across the land parcel, or area of land parcel used for grazing. Land parcels were chosen as the unit of measurement because they provide a readily available boundary with clear ownership or management responsibility. Some steeper land is captured in the areas mapped if the average slope of the whole land parcel is less than 10 degrees.

What are the Water Measurement and Reporting regulations?

The regulations apply to holders of water permits (resource consents) which allow freshwater to be taken at a rate of 5 litres/second or more. The latest regulations came into force on 3 September 2020. The regulations are monitored and enforced by regional councils.

The Resource Management (Measuring and Reporting of Water Takes) Regulations 2010 have been amended to introduce a staged timeline requiring holders of consent to take between five and more than 20 litres of water a second to:

- Measure their water use every 15 minutes,

- Store their records, and

- Electronically submit their records to their council every day.

While the regulations established a nationally consistent regime for measuring water use, they were relatively permissive in terms of reporting water use to the relevant regional council. In addition, the regulations allowed for a range of methods of reporting, and these records could be in either hard copy or electronic formats. In practice, reporting ranged from hand-written records being posted to the council, to excel spreadsheets being e-mailed to real-time time data being sent electronically directly to councils.

The 2010 regulations provided for a staged implementation to manage demand for water meters and verification services. The regulations came into effect for water takes of 20 litres per second or more in November 2012, for takes from 10 up to 20 litres per second in November 2014, and for takes from 5 up to 10 litres per second in November 2016.

In 2016, the Regulations were amended to require water consent holders for every consumptive consented water take over 5 litres per second to:

Have an appropriate measuring device (almost always a water meter) installed

Have the measuring device independently verified by an accredited company (usually an irrigation engineering firm) to ensure the water meter is calibrated to meet the accuracy requirements in the Regulations, and

Provide a continuous record of water use data to their regional council. This data must be provided at least annually in hard copy or electronic formats.

Despite the amendment there is, in many cases, a lack of accurate data for the actual amount taken for many resource use consents. The data supplied to councils has been of poor and irregular quality, which limits how useful it can be. These data quality issues have been identified by the Auditor-General and through the Environmental Reporting Programme.

The 2020 amendments introduce stricter regular measuring and reporting requirements to address these issues.

More detail on the Water Measurement and Reporting regulations is available from the Ministry for the Environment and your local council.